Rare earths and national sovereignty: an impossible equation to resolve?

On November 14th 2025, the CNRS published a collective scientific expert review of the responsible use of rare earths to shed light through an overview of scientific knowledge on the levers likely to reduce France's dependence on these critical metals that are now omnipresent in our daily lives.

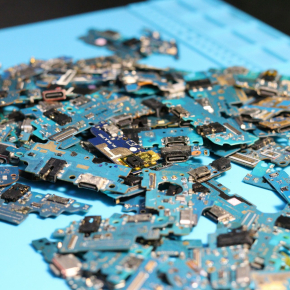

These discreet metals are found in wind turbines, electric cars, computer screens and smartphones and have become essential to the technological tools of today. They are rare earths and there are seventeen of them, all renowned for their unique chemical, optical, magnetic and catalytic properties. As such they have become the subject of a very real modern worldwide 'goldrush'. Since 2015, the world's production of rare earths has increased by an average of 13% per year. Even stronger growth has been observed for the rare earths used in decarbonisation technologies with demand for one, neodymium, doubling in ten years.

However, there is also a significant issue as regards national sovereignty over rare earths as, in the short term, France has no exploitable deposits on its own territory. The same can be said for Europe apart from a few deposits in Sweden and Greenland which means the continent has to depend mainly on foreign imports. In fact, these imports mostly come from China which has established itself as the epicentre of the global value chain, from extraction to manufacturing. China only possesses 35% of the world's resources1 and 44% of the world's estimated rare earth reserves2 but since the 2000s the country has significantly increased its industrial potential to now account for up to 70% of global mineral extraction and 85-95% of refining and processing.

In this context, the CNRS Mission for Scientific Expertise launched a collective scientific assessment of the responsible use of rare earths which involved a group of 17 researchers studying a corpus of over 4000 scientific publications with occasional support from 13 other scientists. The aim of this work was to provide public authorities with scientific information on the existing levers that can be used to reduce France's dependence on these metals which are omnipresent in our daily lives now as well as essential to many sectors of industry.

A sovereignty issue

To escape this Chinese monopoly, European public authorities are encouraging the diversification of supply sources and also the relocation of mines to the Old Continent. These objectives were set out in the Critical Raw Materials (CRM) Act the European Parliament adopted in 2024 and the RESourceEU plan announced by the European Commission President at the end of October last year. In parallel to the European CRM text, France has created an interministerial delegation for the supply of strategic minerals and metals along with a French observatory of the mineral resources used in industry. The issue is closely linked to political sovereignty and economic independence, as Clément Levard, one of the three co-authors of the expert assessment and a CNRS research professor working at the Environmental Geosciences Research and Teaching Centre1 , explains. "The aim of this expert assessment is to study all the levers that can be used to reduce our dependence on external supplies".

- 1Aix-Marseille University / CNRS / INRAE / IRD.

Certain technological innovations have already enabled the reduction of our consumption of rare earths. On example is the optimisation of electric vehicle motors to reduce the quantity of permanent magnets which are mainly composed of neodymium. However, in some cases this substitution has only "shifted our dependence to other critical materials", as Clément Levard points out, citing the development of Li-ion batteries to replace NiMH batteries as an example. Thanks to these new batteries, electric cars can become partially independent of rare earths but this change is driving a new dependence on lithium, cobalt and manganese. Also, technological breakthroughs of this kind remain exceptional because in many finished products, like fibre optics for example, "it's difficult or even impossible to replace rare earths because of their unique properties and doing so may entail the risk of a decline in performance levels", argues the researcher.

Recycling - an Eldorado for industry?

For these reasons, Europe is pushing for diversification in the supply of rare earths rather than trying to replace them completely. However, a few deposits in Sweden and Greenland aside, the European Union has few minerals within its reach which is why the EU is prioritising recycling as an alternative to primary extraction. The public authorities now see recycling as "the main lever for local supply", says Romain Garcier, another of the expert assessment's three co-authors and a senior lecturer in geography at the École Normale Supérieure de Lyon working at the Environment, City, Society Laboratory1 . The aim of the RESourceEU plan is to reuse and recycle critical products and materials contained in European products, including rare earths. Recycling of course offers great environmental benefits, having a significantly lower carbon footprint than primary extraction, but most importantly the idea has vast industrial potential. Despite this, "currently, under 1% of rare earths are recycled worldwide and that figure has remained stagnant since the start of the 2010s", explains the geographer. A few companies have recently announced the launch of recycling projects including the MagREEsource start-up based in Grenoble that derived from research at the CNRS's Institut Néel.

- 1CNRS / École nationale des travaux publics d’État / ENS de Lyon / Ensa Lyon / Université Jean-Monnet / Université Lyon-II Lumière / Université Lyon-III Jean-Moulin.

The potential of this solution is in fact even greater when we take into account secondary sources from industrial waste like bauxite residues or mining waste like coal ash. In Europe, one study has estimated that up to 270,000 tonnes of these metals could be extracted from bauxite residues stored in recent years which would represent 70% of the global production in 2024. This is also the case on the other side of the Atlantic. A recent scientific study in the United States highlighted the fact that coal ash contains around 11 million tonnes of rare earths which corresponds to nearly eight times the US's known national reserves.

However, the Eldorado of urban rare earth mining is not easily accessible because a number of serious obstacles stand in the way of industrialising recycling, starting with the major issue of the dispersion of rare earths in technologies. Romain Garcier has a striking example to share. "Two million smartphones would need to be recycled to gather the same amount of rare earths as in a single offshore wind turbine" so this dissemination of rare earths in small objects like LEDs or mobile phone magnets is in itself an obstacle to collection for recycling. Also, however optimal it may be, recycling is still only likely to solve part of the equation as the co-author admits. "On the global scale, the increase in demand for rare earths is so strong that recycling can't satisfy it on it's own".

The social and environmental challenges facing mines

In addition to recycling and reducing consumption, scientific expertise is also exploring more responsible production alternatives. However, the return of mining to Europe brings up other questions, particularly obtaining the consent of local communities. Pascale Ricard, the third co-author and a CNRS researcher with the International, European and Comparative Law Laboratory1 , points out that the Critical Raw Materials Act "prioritises supply and relocation over environmental and democratic principles". However, she adds that "the relocation of mining activities raises major social and environmental issues. Reopening mines requires a democratic debate on actual supply requirements". Mining law has considerably bolstered consideration for the environment and local populations since most European mines closed at the turn of the millennium and the current idea of a return of mining has already lead to political protests. The legal expert cites the example of the campaign against the lithium mine project in Echassières in the Allier region of France which began as soon as the initiative was announced in 2022.

- 1Aix-Marseille University / CNRS.

To avoid citizen opposition of this kind, the industry could instead turn to the riches of the oceans, particularly the deep seabed. Pascale Ricard explains that "France possesses the second largest maritime domain in the world, covering over 10 million km², and large rare earth reserves are very likely to be present in the French overseas territories". Experts believe these rare earths can be found in polymetallic nodules at the bottom of the oceans. However, the researcher warns that "firstly, the quantities of these reserves are unknown and, secondly, exploiting polymetallic nodules in the deep seabeds poses obvious environmental problems, particularly because this extraction is threatened by a probable moratorium… which France itself supports".

For all these reasons, the three co-authors of the scientific report have concluded that France cannot do without rare earth imports in the immediate future. Clément Levard explains that "moderation in our use of rare earths can help secure national supplies but a holistic approach is required that involves reducing, recycling and producing differently".

For better or worse, our future seems likely to continue being shaped by rare earths.