Disinformation – structuring research and organising defences

Deepfakes, fake news, coordinated social media campaigns... Faced with the growth of information manipulation, the CNRS, the French Armed Forces' general staff and the 'Campus Cyber' have launched a unique initiative with support from the Inria. The project brings together experts, scientists and stakeholders from industry and civil society to develop sustainable tools for society. The series of workshops came to a close on June 25th of this year.

A handkerchief placed in front of the French president on a table. A video of a journalist cut at the wrong moment. Nothing is actually faked here and yet everything is skewed through bias. Manipulation campaigns now operate in reverse by exploiting the truth to sow doubt, the aim being to divide opinion, undermine trust and polarise society. And this to such an extent that in 2024 the World Economic Forum defined disinformation and misinformation1 as the number one global risk, ahead of even climate change.

Faced with this growing threat, the CNRS, the French Armed Forces and the 'Campus Cyber'2 launched a series of interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary workshops3 in autumn 2024 with the support of the Inria to decipher the mechanisms involved, identify scientific and technical blind spots, construct collective resilience and bolster collaboration between stakeholders. This work was completed at the end of June 2025 and constitutes a first step towards constructs an open and decompartmentalised ecosystem of trust that involves academic, institutional and industrial stakeholders alongside civil society in the fight against the manipulation of information.

"Controlling the information environment is now essential to national cohesion", explains General Jean-Michel Meunier, head of the Strategic Anticipation and Orientation Unit of the French Armed Forces general staff, who took part in the afore-mentioned workshops. Information manipulation spreads rapidly like a pandemic thanks to social networks and generative AI. At the core of the system are platforms with their own vested interests. "They have built their empire on the attention economy driven by algorithms that prioritise high-impact content which often plays on emotions and in turn leads to division", points out Anne-Laure Thomas Derepas, head of partnerships and technology transfer at the Institut des Systèmes Complexes de Paris Île-de-France (CNRS). It is essential for us to understand the mechanisms that make this disinformation pandemic possible and anticipate the consequences for individuals and society.

And in our world where everyone has become a relay for information, the impact is systemic. "Ultimately, it all always comes down to one central question – what can I trust?", explains Nicolas Porquet, the CNRS's head of cooperation with the cybersecurity sector. From national defence to individuals – everyone is affected by the phenomenon and France, like other democracies, is still inadequately prepared for this scourge of the 21st century.

- 1Disinformation refers to a person intentionally spreads false information whereas misinformation involves someone spreading false information actually believing it to be true.

- 2A cybersecurity 'totem' hub at La Défense in Paris that brings together the main national and international stakeholders in this area.

- 3Porquet, N. (2025). ' Fédérer un écosystème de confiance en matière de lutte contre la manipulation de l’information', Revue Défense Nationale, 876(1), 82-88.

The first steps towards a collective response

How is manipulated information generated? What makes it go viral? How to respond without amplifying it? And how can we prepare society to resist such information? These four questions were the basis for the structure of the series of workshops. "Up until now, action on this issue has been confined to certain limited ecosystems – academic, institutional, industrial and associative. Here though, we've managed to create a link between these different ecosystems and beyond with the long-term involvement of 250 experts working for the common good", stresses Nicolas Porquet.

Each workshop brought together around a hundred scientists, military personnel, industrialists, associations, journalists and representatives of government departments to discuss and exchange ideas on what is a highly controversial subject. The digital services company Sopra Steria was part of the working group on propagation and virality, working alongside other industrial stakeholders to reinforce the links between academia and private companies. "We'd already created a trusted forum (the Pégase circle) that brings together representatives from the political, academic, media, economic and government spheres but these workshops gave us access to research input that had largely been previously absent from our ecosystem. This means we can avoid duplicating identical actions and progress more quickly working together", explains General Bruno Courtois, Sopra Steria's defence advisor.

The French armed forces consider that this collaboration can act as a springboard for future solutions. "Research can help us characterise threats involving emerging technologies in the same way as it already does with AI and biotechnology", observes General Meunier. Ultimately, these workshops provided an initial overview of current and future challenges but also laid the foundations for a scientific field that remains in its infancy. "High-level multidisciplinary fundamental research that will drive innovation needs to be developed, structured and supported. The development of tools requires understanding of the current threats but also academic expertise also needs to be developed to respond to future challenges in terms of information", insists Nicolas Porquet.

Understanding so we can act more effectively

"Our knowledge of information manipulation is still very much in its infancy in the same way as cybersecurity was a decade ago. Today, we've got to anticipate and organise ourselves", observes Bruno Courtois. And even as we try to understand the threat it is continually evolving. More targeted and subtler attacks can often be undetectable to the naked eye. Generative AI produces misleading but plausible content on the 'industrial' scale. Nicolas Porquet adds that "we need to create an environment that's conducive to reliable information while also guaranteeing freedom of expression".

The example of Operation DoppelGänger gives a good illustration of the challenges involved. This vast pro-Russian disinformation campaign has been active since 2022 in the context of Russia's invasion of Ukraine and aims to undermine Western support for Kyiv by flooding social media with fake articles and false information. Cloned websites, falsified content and generative AI, among other tactics, are being used to impersonate recognised media outlets from 20 Minutes to The Guardian and spread false narratives on a large scale. This campaign simply could not exist without this sophisticated technological infrastructure and indeed demonstrates how modern communication channels are now the backbone of manipulation strategies.

An interdisciplinary response

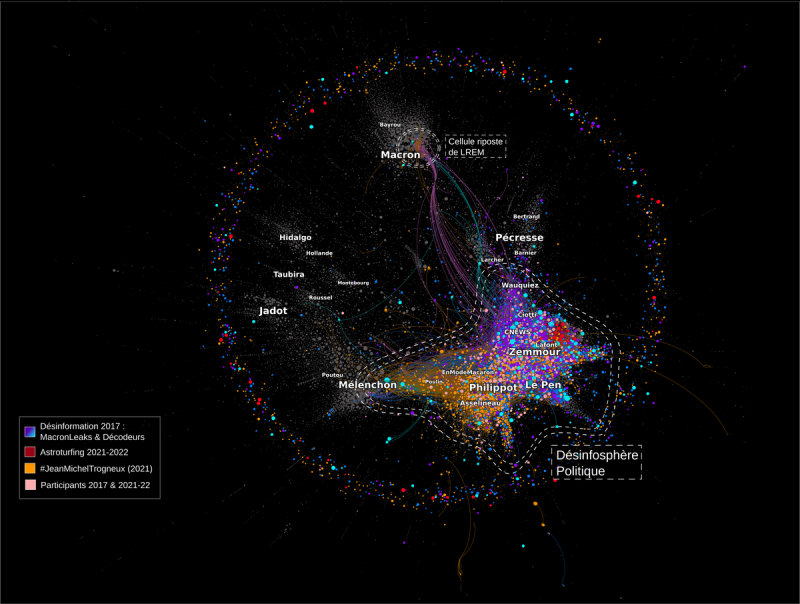

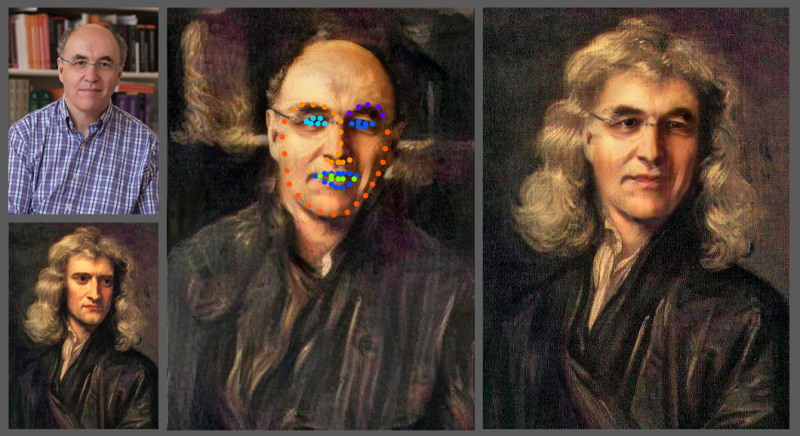

It is necessary to model and analyse masses of data and detect weak signals to understand the viral mechanisms underpinning such a disinformation campaign. To assess a legal threat, law and political philosophy need to be combined and, to build reliable tools, the origin of information has to be identified (through watermarking1 , for example) while developing explainable AI and reinforcing cybersecurity. The Compromis project run in the framework of the Cybersecurity Priority Research Programme and Equipment (PEPR) aims to address the challenges of multimedia data protection by detecting AI-generated content and deepfakes (or hyperfakes).

- 1The principle of watermarking involves affixing a kind of digital signature to content that indicates whether it is authentically created by a human or generated by artificial intelligence. The idea has raised high hopes in terms of traceability but such marking currently remains at the research prospect stage with no scientific consensus on its reliability to date or its prospects for large-scale implementation.

"However, digital detection tools alone will not be enough. Cognitive biases1 are also a real research avenue that's very much worth exploring", explains Anne-Laure Thomas Derepas. This idea can be illustrated, for example, by the bias of continuous influence through which false information continues to influence our reasoning even when debunked. This phenomenon requires a rapid and targeted response without unintended amplification and researchers who attended the workshops have studied methods for detecting coordinated attacks like propagation trees constructed from weak signals. However, by the time the source is identified, the information has often already spread which means the response is still too late.

"Disinformation is above all a human act organised by individuals or groups for social or political purposes", explains Marie Gaille, the director of CNRS Humanities & Social Sciences, one of the CNRS's ten Institutes. "It is part of a deeply degraded information ecosystem that weakens social cohesion and the quality of democratic debate. So, by definition it's a central issue for the humanities and social sciences". Indeed, the very concepts of opinion, information and belief now need to be rethought in our current context of social media and AI. Ethics could also help outline the framework for the countermeasures that are possible in a democracy.

A holistic approach

"Information has to be a common good in our democracies. We need digital analysis tools to model, detect and then counter the propagation mechanisms. Research teams are working on this subject but research into algorithms isn't actually a strategy in itself", warns Adeline Nazarenko, the director of CNRS Informatics. This means that the fight against information manipulation needs to be approached holistically and to integrate different disciplinary perspectives at the crossroads of civil and military issues while also involving research, security and journalism.

- 1These mental mechanisms influence the way we often unconsciously perceive, judge or remember things and can lead us into error.

Given this, the CNRS clearly has a central role to play because of its capacity to combine scientific approaches. As Marie Gaille explains, "mobilising a whole range of skills, particularly in the humanities and social sciences and computer science, means we can hope to analyse this phenomenon and its challenges and then identify effective action levers". The European AI4Trust project involving several CNRS units1 is a splendid illustration of this European multidisciplinary approach. The aim of this project is to strengthen the human response to combating disinformation in the European Union by providing advanced AI-based technologies for researchers and media professionals alike.

Other structuring projects also exist, for example Hybrinfox2 which combines the humanities and social sciences with computer science to work towards both scientific and industrial objectives. Its main research focuses are the identification of vague information likely to introduce or promote bias, online polarisation, information verification and radicalisation. However, major challenges remain in this area including giving structure and the means to act to this still-young scientific community and, above all, for it to continue engaging in dialogue with broader society.

From knowledge to action

In an environment where trust is eroding and truth and falsehood are becoming blurred, "this scientific response is actually a democratic necessity rather than a luxury", insists Nicolas Porquet. However, the best defence will rely on a prepared society rather than on algorithms or laws alone. This requires citizens, teachers and journalists to be capable of identifying, understanding, explaining, demystifying and, ultimately, protecting themselves.

- 1The Centre Marc Bloch (BMBF/CNRS/Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs/Ministry of Higher Education and Research), the Centre for Research in Economics and Statistics (CNRS/École Polytechnique/Genes) and the Centre for the Sociology of Organisations (CNRS/Sciences Po Paris).

- 2Jointly run by the Jean Nicod Institute (CNRS/ENS – PSL/EHESS) and Irisa (CNRS/University of Rennes/Centrale Supelec/ENS Rennes/Inria/IMT Atlantique Bretagne-Pays de la Loire/INSA Rennes/University of South Brittany).

Translating knowledge into tangible responses is therefore one of the major challenges for researchers in the wake of the series of workshops. "We are an institution based on action and all this is only worthwhile if it enables us to act in the real world and, in particular, to gain the upper hand over our enemies", emphasises General Jean-Michel Meunier. For example, research into social media is already producing real-world results in certain disinformation campaigns.

The series of workshops that ended in June has paved the way for a multi-stakeholder ecosystem by revealing the scale of the challenges and the urgent need for more research. Now, a coherent and shared approach will be key to strengthening our collective resilience and, in this sense, the ASTRID 'Resistance' call for projects1 launched by the National Research Agency and the Defence Innovation Agency last June is a first opportunity to capitalise on this momentum and drive academic research on the issue of citizens' resistance to information manipulation.

- 1Specific support for research and innovation in the field of defence.