For geoengineering expertise founded on responsible research

At the end of September 2025, the 'Climate, Biodiversity, Sustainable Societies' programme agency steered by the CNRS published a working paper on climate interventions. The mission's project manager explains why scientific expertise is required in this controversial research field.

Towards the end of September, you submitted a document on climate interventions to France's Ministry for Ecological Transition. This was managed by the programme agency the CNRS was asked to lead. Where did the idea originate?

François Ravetta1 : A few months ago, the 'Climate, Biodiversity, Sustainable Societies Agency' began working on a project on climate interventions, or 'geoengineering' as it's more commonly known. The aim is to develop a national roadmap to determine which research needs to be carried out in this area, taking political, economic and ethical issues into account, along with questions of sovereignty and national security. The agency wants to address the climate interventions issue by moving beyond climate science and promoting a multidisciplinary approach to bring together research teams in this area with often limited research resources. In this way I was able to put together a group of eighteen experts with varied profiles from a dozen research organisations.

This mission interested the Ministry of Ecological Transition's research sub-directorate which acts as the national focal point for IPCC negotiations. More specifically, the sub-directorate requested that we provide scientific expertise to support its positions during international negotiation cycles, primarily in the area of marine CO₂ storage. The framing letter was ambitious which initially led three of our colleagues from the expert group to draft a working paper summarising the state of the art along with the associated techniques' potential and risks. At the end of 2026, we'll be delivering a comprehensive prospective report that's been extended to cover all techniques for removing the CO₂ that's built up in the atmosphere.

Why focus on CO₂ storage to this extent?

F. R.: This technique is also known as Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR) and involves removing carbon from the atmosphere on the global scale to try to limit ongoing global warming. In this way we're working on the cause of climate change – excessive CO₂ in the atmosphere. To work towards achieving carbon neutrality, the IPCC has already partly integrated this into certain of its scenarios in the form of negative CO₂ emissions.

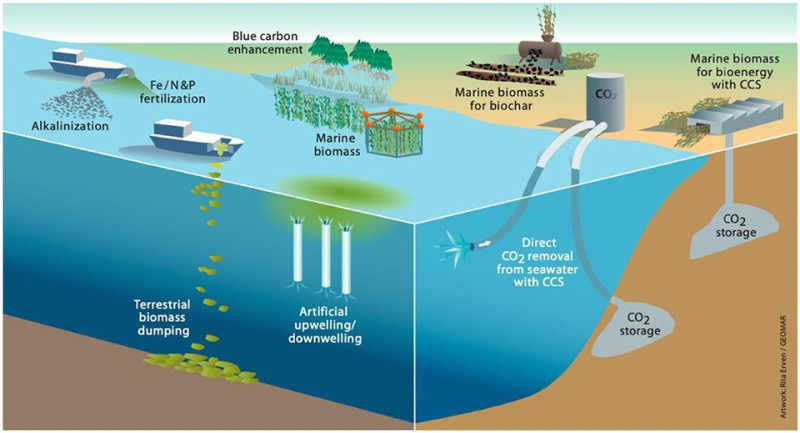

In practice, CDR can be carried out both at sea and on land through the use of either biological techniques or physical and chemical resources. For example, at sea, the mass growth of underwater algae or alkalisation of the ocean2 is under consideration to increase their capacity for CO₂ capture. On land, ecosystemic carbon sinks (agricultural areas, forests, wetlands, etc.) and also geological processes like underground reservoirs are used.

The different issues with marine CDR are its technical feasibility, scalability and energy cost along with, by extension, its economic relevance and impact on the marine environment. These technologies have real potential as long as scaling up such tools is based on the use of carbon-free energy. Their overall positive effect worldwide will depend on the effective control of the associated environmental risks as there is a risk that the solution proposed will cause more disruption than improvements without such safeguards.

- 1Project Manager for Climate Action and Sustainable Societies with the 'Climate, Biodiversity, Sustainable Societies' Programme Agency and professor at Sorbonne Université's Laboratory for Atmospheres, Observations, and Space (CNRS / Sorbonne Université / Université Versailles-Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines).

- 2Increase in an environment's pH through the addition of a base or an alkaline compound.

Geoengineering may once have been considered to be science fiction but in recent years it has gained credibility among policy makers and some scientific communities. How can this shift be explained?

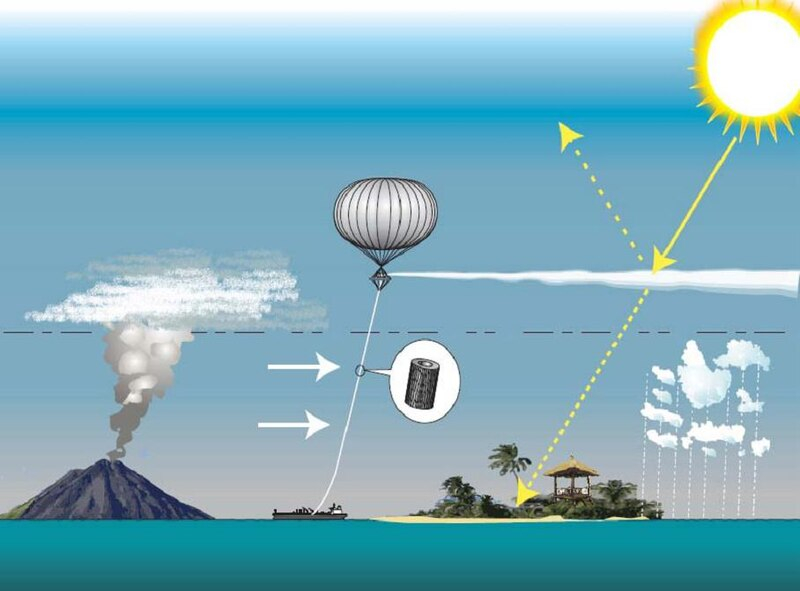

F. R.: Carbon removal techniques are already integrated into climate trajectories, particularly the IPCC's, but this isn't the case for the other aspect of geoengineering – solar radiation management (SRM). SRM techniques don't address the accumulation of CO₂ in the atmosphere, which is the root cause of climate change. Instead they deal with its consequences, namely rising temperatures, which we're attempting to counteract by injecting aerosols into the stratosphere. The idea here is to cool the planet through a parasol effect as with the most powerful volcanic eruptions. This is a controversial technique because it modifies the climate to a new unknown state that's potentially problematic. For example, monsoons in India could be disrupted and there's also a risk of terminal shock, i.e. a rapid rise in temperatures if aerosol injections are suddenly stopped.

However, there are currently no serious plans to roll out this technology and studies on the subject remain mainly academic in nature. However, using SRM seems to be on the agenda for various stakeholders. The Climate Overshoot Commission made up of former politicians presents SRM as a path to explore as a response to climate change. The British risk research agency, the Advanced Research and Invention Agency, recently launched a call for proposals to finance SRM projects with an experimental component. France had always refused to follow this idea until now.

We're also seeing changes in civil society, particularly among younger people in regions exposed to the effects of climate change. One example is the Finnish association Operaatio Arktis which is calling for research into SRM to help preserve the future of future generations. More broadly, we're also seeing the emergence of competing narratives about geoengineering which has been negatively associated with techno-solutionism, climate modification and even climate control. Geoengineering is thus being transformed into a set of climate interventions with the imagery of care or emergency medicine used to support the term.

Who is promoting geoengineering on the global scale?

F. R.: An increasing number of countries are taking an interest for varied reasons. These include countries whose wealth is based on the extraction of fossil fuels or those which need time to transition towards renewable energy. This is understandable but there's also a risk of rushing headlong into the future because the most effective policy for combating climate change is to reduce emissions of carbon dioxide. Some countries are also working on putting geoengineering on the international agenda. Switzerland, for example, has unsuccessfully campaigned twice for the UN to take up the issue of studying geoengineering's risks and opportunities on an official basis. In this case, Switzerland's motivation was more to defend an open and multilateral approach to the issue and avoid a sudden unilateral and uncontrolled rollout than to defend Swiss economic interests. Finally, the climate issue is increasingly being viewed from the standpoint of national security and sovereignty, the aim being to anticipate or guard against a rival state ending up in control of the climate. This approach is rendered necessary by a geopolitical context in which national interests are tending to prevail over multilateralism.

For its part, like most other European countries, France, defends the position of the Paris Agreement, namely to drastically reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and so is very cautious about geoengineering techniques. This leads to the question of how France and Europe can assert this position.

Two scientific reports involving geoengineering have published in recent months. Firstly, there was the opinion given by the CNRS Ethics Committee (Comets) on the responsibility of certain high-risk research. Secondly, there was the recent French Academy of Sciences report condemning all research into geoengineering. How do you assess these reports in the context of your own prospective work?

F. R.: These are useful reports because they define the scope of which research is possible or acceptable. The Comets recommendations are in line with European positions and recommend that geoengineering research should not be carried out at the expense of other research aiming to combat global warming. They also advocate for no SRM experiments to be conducted in the field and for a multidisciplinary approach. Of course, the risks associated with geoengineering required Comets to stress the precautions to be taken and advocate for civil society to be consulted. I think we could draw inspiration from medical research's practices and rules to regulate geoengineering research.

The Academy of Sciences report gives an overview of current knowledge and makes recommendations. It's an interesting starting point for our expert group as long as it's complemented by an analysis of geoengineering from a humanities and social sciences standpoint. I don't agree with the recommendation that dedicated research on SRM is not legitimate, firstly because dedicated research is necessary to answer certain questions like the governance of SRM, which is potentially a source of conflict. Secondly, the lack of research on this subject has led to a corresponding lack of expertise which in turn weakens our position in European and international negotiations.

At the end of the day, should research into geoengineering be carried out or not?

F. R.: Firstly, we need to distinguish between CDR and SRM. While atmospheric carbon removal techniques aren't a panacea, it's still highly likely they will be rolled out which bring up the issue of research that's linked to the emergence of a new economic sector. From this standpoint, some of our European partners are already taking action and it would be a shame if France didn't capitalise on its strengths in this field.

As for SRM, the issue is mainly strategic at this stage. We need to anticipate possible futures, including the scenario of unilateral deployment, and give ourselves the means required to assert our interests or even to intervene. So this all means research to support expertise is actually necessary.

Secondly, we also need to take the heat out of the debate about geoengineering. It's not a question of opposing an ethic of conviction – which could lead to a loss of expertise – and an ethic of responsibility that could potentially be subordinated to political or economic demands that minimise risks. Instead we really need to strike the right balance. Research into geoengineering is risky and we have to draw the necessary conclusions so we can obtain responsible expertise on the subject.