The societal impact of research – a new priority project for the CNRS

How can the tangible impact of research on everyday life be effectively measured beyond just the actual discoveries involved. At a conference held on September 5th to present the CNRS's first societal impact study, the organisation unveiled a new approach to the analysis and promotion of science's contribution. Interview with Catherine Dargemont, the head of the CNRS's Impact Mission and, indeed, of this initiative.

Why has the CNRS now opted to commit to societal impact studies?

Catherine Dargemont: The impetus for this initiative derived from recommendations by the High Council for the Evaluation of Research and Higher Education's (HCERES) assessment committee but the CNRS's ambition was already to equip ourselves with robust tools to help demonstrate and convince people of the importance of science - and particularly of the CNRS - for society. This aim of this initiative is to analyse the impact of research that's been carried out, covering all its cultural, social, environmental, health, economic and political dimensions including any more unexpected or controversial aspects. The idea is not just to produce inspirational or success stories but to document all the effects of research, be they positive or negative. We also need to situate our results in a broader and more intelligible context for different audiences, particularly public decision-makers, so they can benefit from them for their strategic orientations and choices.

How does this approach go beyond simply 'measuring'?

C. D.: The main aim of this approach is to use retrospective analysis to inform foresight studies. These impact studies are tools for improvement that can also illustrate show how well an institution is doing in achieving its objectives and missions. It's essential to understand the path that scientific results take - from questioning by scientists to their research's observable effects on society. The first step is therefore to describe the effects of research on society accurately and, when relevant, quantify such effects, rather than just producing figures for the sake of it. We use case studies to find out more about how the CNRS' characteristics (long-term research, multi- and interdisciplinary approach, national coverage, international influence) contribute to the major short-, medium- and long-term societal impacts of our research and how these are essential for driving sustainable change. As well as these objectives in terms of evaluation, self-assessment, improvement and communication, we also hope these case studies can serve as tools to support public policy-making and provide reliable, nuanced information to influence public debate.

Which method did you select?

C. D. It really was crucial to adopt a methodology that would enable us to achieve our objectives. We analysed the various approaches used and then chose and adapted for the CNRS an approach designed by researchers1 that has been published in international journals and used for over a decade in agronomy and increasingly in other fields. This consists of defining the precise chronology of the case studied, analysing and documenting what we call the 'impact pathway' which refers to the 'Inputs' or resources used, the 'Outputs' or scientific productions, the 'Intermediaries' or stakeholders who appropriate a research product to transform it, and the 'Impacts' or effects on society. Finally we deduce the basis of an 'impact radar' for the different societal dimensions involved. To do this, we combine all the available written (bibliographies, activity reports, information provided by scientists, various other reports), audiovisual (including online conferences) or digital (scientific literature databases, patents, funding, press, public policy documents, etc.) documentation and also carry out semi-structured interviews with all stakeholders. The advantage of this approach is that it can be applied retrospectively to research carried out over the past 20 or 25 years on a given subject, and also in terms of foresight by supporting major projects with predefined impact objectives so they can drive the desired transformations.

Can you give a tangible example?

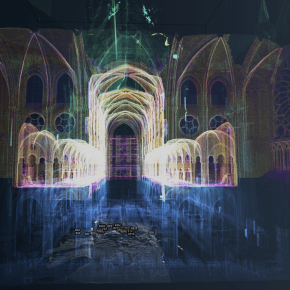

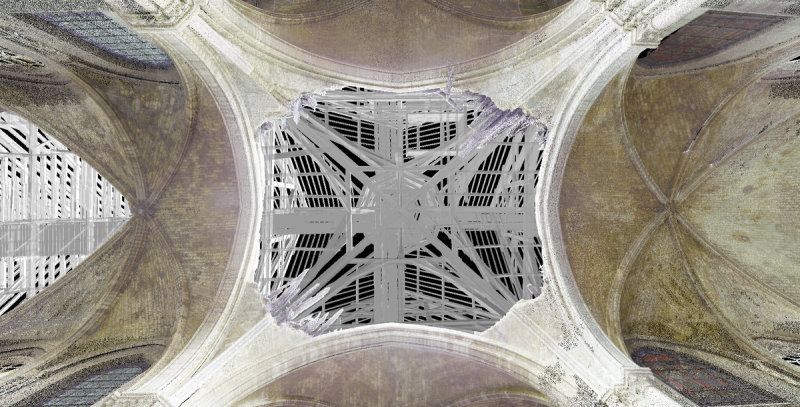

C. D.: Our first emblematic study was of the research carried out following the fire at Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris. Just eleven days after the disaster, the CNRS set up a scientific task force which was an example of exceptional reactivity. The impacts of this scientific project run jointly by the CNRS, its academic partners and the French Ministry of Culture were found to be manifold. On the scientific level, this project completely renewed the body of knowledge on Notre Dame, helped structure heritage sciences by involving various disciplines - with digital technology research playing a decisive role - and laid the foundations for scientific support for the supervisory authorities and project managers of restoration projects. On the cultural level, the experience of the Notre-Dame scientific project involving a restoration of such magnitude has already become an international benchmark for the scientific management of a heritage crisis as regards its impacts on restoration and its practices and on the public whose interest in heritage has of course been amplified. Documentaries on the scientific project have been viewed 17 million times! Furthermore, this renewed perception of heritage is already feeding into conservation policies. Research into using green wood for roof frames could eventually lead to regulatory changes through building standards. Research into lead pollution has provided reliable data on contamination and possible solutions which have informed the implementation of monitoring processes for the pollution that historic monuments emit.

- 1The ASIRPA (Analysis of the Societal Impacts of Research) method developed by the National Research Institute for Agriculture, Food and Environment (INRAE).

What are the next projects?

C. D.: We're currently completing a study of the societal impact of battery research to be released to the public on December 8th. This is a strategic issue for energy transition and industrial sovereignty alike. Of course, we used the same methodology as for Notre Dame and added a quantitative analysis of the economic impact and, above all, the return on investment. There have been some surprising results but I'm sure you won't mind if I keep the suspense going a little! Also, we plan to support projects with high potential impact from the outset which means we can integrate impact considerations in real time rather than just retrospectively.

Can this work involve the entire scientific community?

C. D.: That's one of our biggest challenges. It would be unrealistic to aim to measure the overall impact of all CNRS research which is why we've opted to move forward with case studies. But these studies only make sense if they're developed with our researchers who need to see them as an opportunity to put their work into perspective and produce a foresight tool rather than an administrative constraint. For this, we're emphasising dialogue and tangible demonstrations of what evaluations like this can offer in terms of greater recognition of their work, greater influence on policy directions and increased visibility among our partners and the general public. The symposium on September 5th bringing together both public decision-makers and scientists and represents a significant step forward in sharing this vision both internally at the CNRS and externally.