The Year of Engineering – promoting vocations to construct a sustainable future

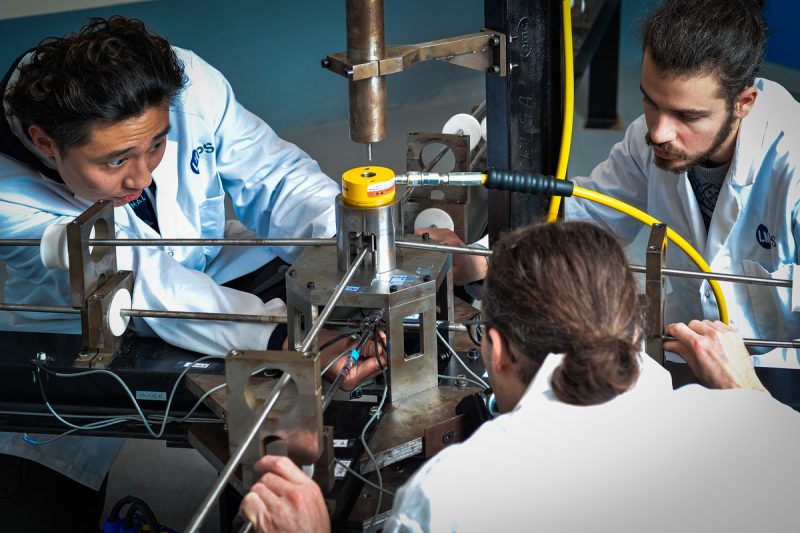

Following chemistry, biology, physics and geosciences, it is now engineering's turn to have its own thematic year which will run from September 2025 to June 2026. Lionel Buchaillot, the director of CNRS Engineering, reveals the year's objectives on the eve of its launch.

The CNRS's new thematic year features engineering. What are its objectives?

Lionel Buchaillot: This initiative derived from a shared observation made by the CNRS and the National Academy of Technologies of France. In many sectors, industries have realised that a great number of engineering students end up working in another sector after finishing their training. This loss of young graduates results in a shortage of labour at all levels – industries lack workers and technicians as well as engineers and PhD graduates.

However, although one of the government's priorities is the reindustrialisation of France, this can't be achieved without training new engineers. Therefore, this Year of Engineering run in partnership with the Ministry of National Education, Higher Education and Research aims to showcase all engineering professions, ranging from those qualified with a CAP vocational training certificate1 to those with PhDs.

In fact, of all the scientific disciplines, engineering is the least represented in the school curriculum...

L. B.: It is indeed a subject that's rarely or never taught, except in specialised courses. It is introduced in secondary school through technology classes but engineering as a subject only arrives very late in secondary schools with the 'Engineering Sciences' option in the '1ère' year2 . And even then, this option is only taken by 3% of students and these are mainly boys.

The aim of the Year of Engineering is to create a continuum from school education to the industrial sphere through educational days for teachers – from primary school to secondary school level and even teachers of 1st year primary school classes.

Given these circumstances, how can such little-known professions be made more attractive?

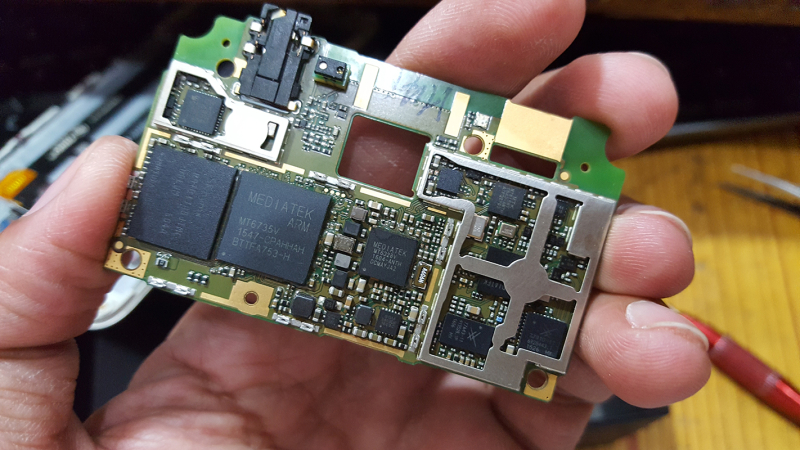

L. B.: These days, everything is done to make engineering invisible. The ergonomics of the devices and machines we use actually conceal the complex processes within them. Behind their apparent simplicity, our phone screens contain a whole lot of electronics... and therefore a whole lot of engineering work. And yet some wonderful professions are there to be discovered behind what's hidden. To make sure nuclear power plants run smoothly, we need excellent, skilled boilermakers.

On this point, the Ministry of Education has been paid particularly attention to how the world of work is represented in our training programmes. It's difficult to revitalise certain industrial sectors because we've lost the know-how of previous generations of workers and this means we need to train new ones while reinventing the technical skills these industries require.

That's the challenge of the 'Retour dans mon collège' ('back to early secondary school') initiative that we're launching in the framework of this thematic year. This simply involves inviting people who work in engineering, whatever their profession, back to their old schools. Meetings like this are very important in helping secondary school pupils decide on their future careers because they offer direct contact with those professions. People may encounter teachers and medical professionals on a daily basis but we see very few electronics engineers or people in other engineering professions.

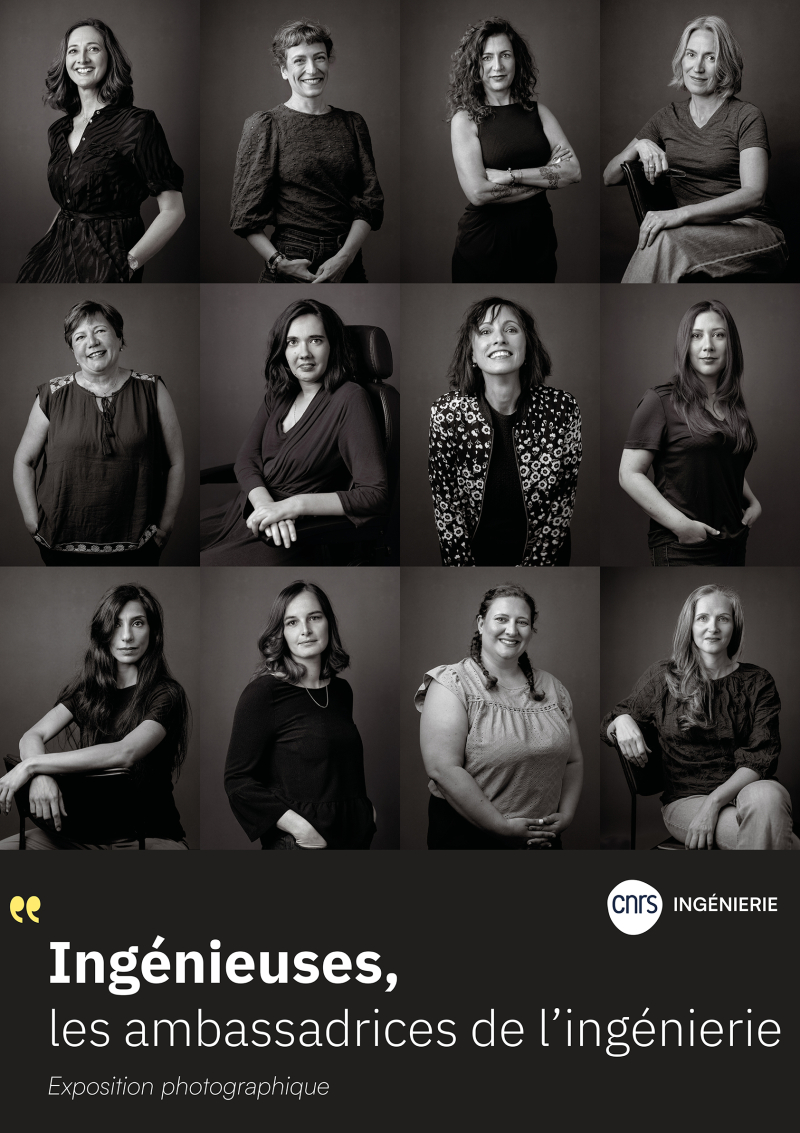

Engineering professions also suffer from an under-representation of women so, to attract people to these fields, your Institute is launching a new travelling photographic exhibition, 'Ingénieuses'1 , during the Year of Engineering.

L. B.: This exhibition was inspired by the observation that there are very few women in engineering, in both its industrial and scientific branches. Hélène Barrès, the new gender equality officer at CNRS Engineering, recently carried out an internal study that confirms the predominance of male engineers. Our institute has 71% men and 29% women. Also women are under-represented in positions of responsibility – for example only 17% of CNRS unit directors are women – and, conversely, over-represented in administrative jobs. Overall, the gender equality index2 is 2.42 which means CNRS Engineering is one of the least feminised institutes at the CNRS.

These figures can be explained by what is already a very small initial candidate pool. The highly stereotypical nature of technical education leads to young girls rarely imagining themselves becoming engineers later. In fact, in their final year of secondary school when they have to choose an option for their baccalaureate 46% of female students give up on science. This means we need to change things a long while before students reach engineering schools, which are predominantly male, and introduce young girls to these career paths and professions by promoting the appeal of engineering to them right from primary school. That's why we're working with scientific outreach associations who work with young audiences like 'La Main à la Pâte' and the CGénial contest.

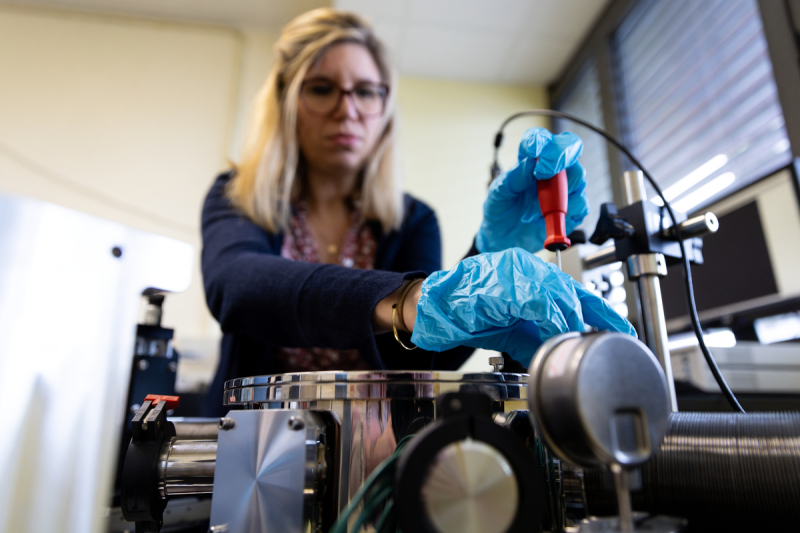

As well as a round table discussion dedicated to the subject, the inauguration of the Year of Engineering on October 1st at the Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac Museum in Paris will see the launch of the 'Ingénieuses' exhibition. This photo exhibition was inspired by the 'Science Taille XX Elles' exhibition and showcases female role models in science that young girls can identify with. To do so, we're promoting a positive and attractive image of engineering sciences for women. The new exhibition and its ambassadors will tour CNRS laboratories and schools after its opening.

This year's sub-theme is 'Building a Sustainable Future'. What role can engineering play in the environmental transition?

L. B.: All too often, engineering is still seen as actually contributing to climate change. And with good reason, really. Although they've begun to decarbonise, certain industries like steelworks, cement works or glassworks, for example, are still high CO₂ emitters. This reality and the negative image that goes with it are hindering the recruitment of younger generations and contributing to labour shortages in this sector.

Consequently, engineering needs to question its own sustainability in terms of energy and resources while also prioritising recyclability. This is particularly beneficial for a country like France which is relatively poor in mineral resources. CNRS Engineering has already started out on this path. In early 2025, we set up a new support and research unit called Utopii1 that's dedicated to life cycle analysis. This involves calculating a product's environmental footprint from the extraction of raw materials to the treatment of its waste. Utopii produces data and guidelines for our laboratories on their research's social and environmental consequences. Alongside this, we've co-authored an engineering ethics charter with the National Academy of Technologies. This charter questions the responsibility of the industrial applications of our research, for example in fields like armaments or biotechnology.

Ultimately, engineering does have a role to play in the environmental transition. Let's take blackouts – massive and prolonged power failures – as an example. As a corollary to decarbonisation, the electrification of society relies on the intelligent management of electricity grids to optimise the consumption and transport of electricity from renewable energy sources. We would quickly face blackouts without the complex engineering behind this management. As well as the consequences for people's daily lives, every hour of power outage means an actual loss of GDP. Here again, engineering professions are everywhere even if we don't see them.

- 1A transdisciplinary unit providing guidance and forecasting regarding the environmental impacts of engineering research (Aix-Marseille University / CNRS / Ensa / École des Ponts / Insa / Sorbonne University).